Category

All the Right Moves

Jefferson’s Movement Disorders Center Takes Top Honors

It is September 26, 2018, and Jim McKenna is sitting on the edge of the exam table, waiting for the doctor to arrive. His left hand is shaking uncontrollably, his right hand only slightly less so. At today’s consultation, the 76-year-old will learn the details of his upcoming brain surgery. In spite of the somberness of the topic, McKenna has an upbeat attitude, a mischievous gleam in his eye, and a wickedly dry sense of humor. Even Parkinson’s disease can’t take that away from him.

McKenna, from Warwick, Pennsylvania, will undergo deep brain stimulation (DBS) surgery in a few weeks to alleviate the ever-increasing symptoms of Parkinson’s disease—including tremors and stiffness—and he will do it under anesthesia. That’s not unusual for most surgeries, but it is for DBS, which is traditionally performed while the patient is awake.

“Doing the surgery under anesthesia alleviates a lot of stress for the patients,” explains neurosurgeon Chengyuan Wu, MD, MSBmE, who will perform the operation. During DBS surgery, leads (wires with tiny electrodes) are implanted in a specific area of the brain. The leads are attached to a wire that runs under the scalp and beneath the skin of the neck, and is connected to a neurostimulator just below the collarbone under the skin. Like a pacemaker, the neurostimulator delivers electricity to the lead, which normalizes brain signals in the affected areas. This regulates the abnormal brain cell activity, and can greatly reduce symptoms.

Jefferson was among the first medical centers in the country to offer the asleep technique.

“We strive to offer novel treatments and surgical techniques, complementary therapies, and pioneering research and clinical trials for our patients with Parkinson’s disease and other movement disorders,” says Daniel E. Kremens, MD, JD, co-director of the Movement Disorders Program.

Approaching neurological disorders from many different vantage points is what sets Jefferson apart from other institutions, says Richard J. Smeyne, PhD, director of Jefferson’s Comprehensive Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders Center at the Vickie and Jack Farber Institute for Neuroscience – Jefferson Health. It has earned the Movement Disorders Center recognition from the Parkinson’s Foundation as a Center of Excellence, an elite designation reserved for just 34 centers in the U.S. and 48 worldwide.

Jefferson’s three-year-old center, a nationally recognized facility for patients with Parkinson’s disease and Parkinsonism, dystonia, Huntington’s disease, tremors, ataxia, and tics or Tourette’s syndrome, received the designation in August 2019. Smeyne says that collaboration among all departments at Jefferson—both inside and outside the Vickie and Jack Farber Institute for Neuroscience—helped the center become the youngest ever to achieve the designation.

“Neuroscience is a multidisciplinary field,” says Smeyne, who received his PhD in neuroanatomy at Jefferson in 1989. “It’s great to have all disciplines together under one umbrella so that you can have within one center all of the expertise and viewpoints you need for the full picture.” Viewpoints, he notes, are just as important as expertise, as seeing all the different sides of an issue—clinical, research, patient care—helps each participant better understand what is needed to accomplish a goal.

To that end, Smeyne takes his graduate students out of the lab, bringing them into the operating room to watch DBS surgery and into the clinic to observe movement disorders specialists working with patients. He also invites neurology and neurosurgery residents into the lab to conduct research.

“We have four basic science labs here at Jefferson that are studying Parkinson’s disease, and we do not work in isolation. We are in constant communication with the clinicians, and they are in constant communication with us,” Smeyne says. “It’s a powerful program that really integrates what a true center of excellence is—not by thought, but by deed. After all, we are not here to solve Parkinson’s in mice—we are here doing work to better the condition of humans.”

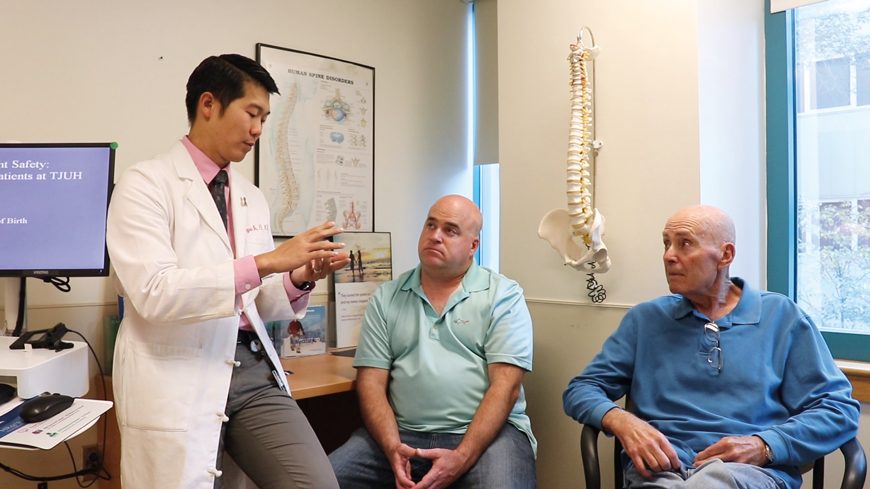

Chengyuan Wu, MD, MSBmE, James (Jim) McKenna Jr. (son), and Jim McKenna

Chengyuan Wu, MD, MSBmE, James (Jim) McKenna Jr. (son), and Jim McKenna

The Parkinson’s Journey

Jim McKenna’s Parkinson’s journey began six years ago when he noticed the telltale signs of the disease. First, his pinky began to twitch; then his arm began to tremor; eventually the involuntary and uncontrollable movements migrated to other parts of his body. As the symptoms got worse, he sought medical care with Kremens.

McKenna began taking medication, and later signed up for Rock Steady Boxing, a noncontact exercise program that focuses on balance, strength, agility, motor skills, and flexibility for Parkinson’s patients. Over the past few years, clinical studies have shown that vigorous exercise is neuroprotective in animal models of Parkinson’s disease. The research into the effects of exercise on Parkinson’s began 15 years ago in Smeyne’s laboratory in the Department of Developmental Neurobiology at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tennessee, and came with him to Jefferson.

“While we know exercise doesn’t cure the disease, recent studies have suggested that vigorous exercise might slow the progression, while other studies show that exercise can greatly improve quality of life,” Smeyne says.

While the combination of medication, boxing, and other daily exercise helped McKenna for a while, as time wore on it became increasingly apparent he would need more. Kremens suggested DBS.

“What do you hope to get out of this surgery?” neurosurgeon Wu asks McKenna during the DBS pre-op visit.

McKenna thinks for a moment, looks at his trembling hand, and says, “I guess I shouldn’t expect to be able to put electrodes in someone’s head.”

“So your surgical career isn’t taking off right now?” Wu teases.

“Nah, it’s been a little slow,” McKenna shoots back.

For all the joking and levity in the exam room, Parkinson’s is no laughing matter, and McKenna is pinning a lot of hope on the surgery. Of all the things DBS promises, the patient says the most important thing to him is simply to regain the ability to write. “I want to be able to sign my name again.”

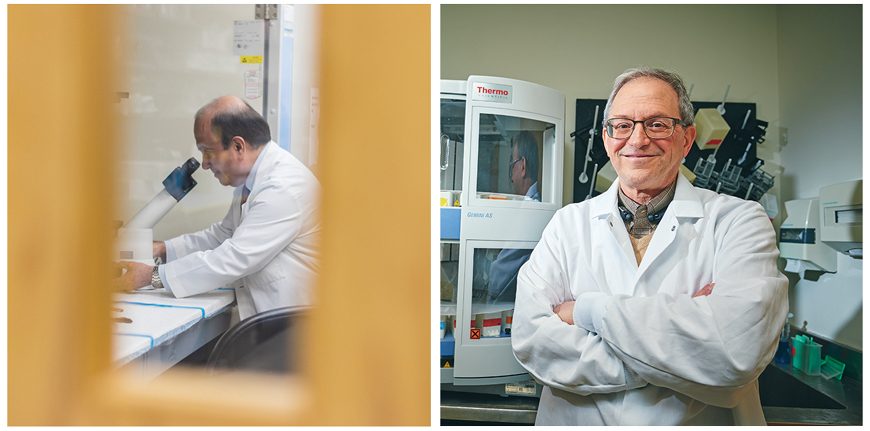

Richard J. Smeyne, PhD (left) and Abdolmohamad Rostami, MD, PhD (right)

Richard J. Smeyne, PhD (left) and Abdolmohamad Rostami, MD, PhD (right)

“Because There Was a Need”

The Jefferson Movement Disorders Center was born out of the Movement Disorders Program, the brainchild of Abdolmohamad M. Rostami, MD, PhD, chair and professor of the Department of Neurology and director of neuroimmunology and the multiple sclerosis laboratory.

“Parkinson’s is a very common neurological disease,” says Rostami, explaining that, like many neurological diseases, Parkinson’s is a “disease of aging.” As the population ages, the need for care, specialists to administer that care, and research to find better ways to treat—and possibly cure—the disease is central to the goal of his department.

The Parkinson’s Movement Disorders Program was created “because there was a need for it,” he says.

According to the Parkinson’s Foundation, more than 10 million people worldwide are living with the disease. In the United States alone, approximately 60,000 are diagnosed with it each year. In addition, a recent study by the foundation predicts that by 2030, an estimated 1.2 million Americans will be living with Parkinson’s.

“The disease affects about 2% of all people over 50 years old, and that’s only going to be getting greater as our healthcare gets better and people live longer,” Smeyne says, adding, “It is a disease that affects everyone. It knows no boundaries—not socioeconomic, religious, racial, or anything else.”

In 2005, Rostami reached out to neurologist Tsao-Wei Liang, MD, and invited him to join the department; a few months later, Liang reached out to Kremens, who had completed a residency in neurology followed by a fellowship in movement disorders.

“It was an exciting opportunity to get in on the ground floor of something new,” says Kremens, a third-generation Jefferson Medical College (now SKMC) alum.

Together, they built the program that would eventually lead to the creation of the center, providing care for an increasing number of patients.

While the center treats those with a multitude of movement disorders, the majority of the patients have Parkinson’s, Smeyne says. “It is the second most common neurodegenerative condition in the world—just behind Alzheimer’s—and it’s growing fast.”

In the early days of caring for patients at Jefferson, Kremens and Liang became involved in clinical drug trials and device trials, eventually teaming up with Ashwini D. Sharan, MD, director of functional neurosurgery and the Neuroimplantation Center, to create a DBS program. Wu came a few years later, bringing with him the asleep DBS expertise.

Soon, other pieces of the Movement Disorders Center puzzle began falling into place. The next step was to collaborate with those in basic science, including researchers such as Lorraine Iacovitti, PhD, who had been conducting studies in understanding how neurons differentiate into dopamine neurons during development of the brain.

The problem, says Kremens, was that the components were working independently of one another: “It was clear the departments needed to integrate.”

To do that, Jefferson recruited Smeyne, who had been studying the cell biology of Parkinson’s disease at St. Jude.

“He helped coordinate all the efforts—the clinical, the research both at basic level and clinical level, the patient care—bringing them all together. Once we had that, Jefferson designated us as a center,” Kremens says.

Throughout the years prior to the designation as a center, personnel were added, including a nurse practitioner, an administrative assistant, and a social worker. A fellowship program was established, and Jefferson’s neurology residency program grew to become one of the largest in the country, with 27 residents.

“It’s truly comprehensive in terms of neurology, neurosurgery, basic research, and rehab. We are focused on doing the work with the ultimate goal of helping the patient,” Smeyne says. “And that’s why we do everything we do—to help the patient.”

Currently, the components of the Movement Disorders Center are located in several places on the Center City campus, but future plans include expanding services and bringing everything under one roof—a kind of one-stop shopping center that would geographically bring together clinical services, rehabilitation therapies (physical, occupational, and speech), and research.

Care to Cure, a grassroots group of Movement Disorders Center patients and their families and friends, is spearheading fundraising efforts to help the new center become a reality—something Rostami says he is looking forward to.

“As quickly as we have grown, so has the list of patients waiting to be seen,” he says.

Hope Ahead

In October 2018, McKenna underwent the three‑hour DBS surgery; a month later, the physicians and nurse practitioner began the process of programming the unit.

“DBS programming requires patience,” Kremens says. “Unlike what patients see on TV or the internet, where results often appear instantaneous after surgery, results from DBS can take up to six months of programming sessions. However, once the programming is completed, most patients need follow-up appointments only twice a year.”

By April 14, 2019—the sixth and final visit to tweak the programming—McKenna is more relaxed than in previous visits. With Sheila, his wife of 57 years, by his side in the exam room, he is pleased to report his progress. His tremors are greatly diminished. His gait is smoother. He is sleeping better. He is looking forward to spending time at his family’s summer home on Lake Champlain and taking the helm of his boat for the first time in four years.

Six months later, at an October 9, 2019, visit to the doctor, McKenna reports that his summer was everything he had hoped it would be. The best part, he says, was being able to take his Zodiac out on the water while two of his grandchildren rode WaveRunners alongside him.

“It was freedom,” he says of his ability to get back out on the boat. He is grateful for the care he receives at Jefferson that makes his progress possible—progress that includes being able to sign his name again.

McKenna knows the DBS surgery is not a cure. Neither is the medication. Nor the Rock Steady boxing. But all those things together have given him back much of what Parkinson’s robbed from him. And he is optimistic that ongoing research will provide breakthroughs that will continue to improve his life.

When asked what he would say to someone who just found out they have Parkinson’s, McKenna thinks for a moment, then smiles. “What would I say to them? I’d say there’s hope ahead.”